Quantifying Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers: Drug Impact and Bioanalysis in New Chemical Entity Development

January 11, 2024

Home > Veeda Insights > Evolving Clinical Development Regulatory Framework in India

India is emerging as a country with tremendous potential to contribute to the national and international clinical trial platforms.

The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) is the national regulatory authority of India managed by the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI).1,2,3

The DCGI is responsible for the coordination of inspections of the sponsors, manufacturing units, as well as trail sites.3

In 2000, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) set up ethical guidelines for conducting biomedical research on human subjects.4 The year 2005 saw a revision of Schedule Y of the Drug & Cosmetics act, 1945, to align Indian regulatory laws to definitions and procedures that are internationally accepted.

The changes included:

India also signed the trade-related intellectual property rights (TRIPS) agreement in 2005 in order to open up the prospects for conducting more clinical trials in India.5

Apart from harmonizing the regulatory acts to international standards, India quickly became a favorable destination for clinical trials as it offered:6

Despite changes in the regulations, many multinational pharmaceutical companies took advantage of the large population that had either inadequate knowledge about clinical trials or were illiterate. In addition, an ill-defined healthcare system added to the challenges of monitoring unethical practices.

This led to conducting clinical trials with little supervision, and no recording of patient informed consent either in written or as audio/visual content.

Patients were administered investigational drugs or devices without disclosing known serious adverse effects, some leading to the death of the subjects. Moreover, no independent enquiry committee was set up to ascertain if the death of the patient was related/not related to the investigational product or device.4

The years 2010 to 2013 saw a trying phase in the Indian clinical trial scenario due to the accumulated ill effects of conducting unethical trials.

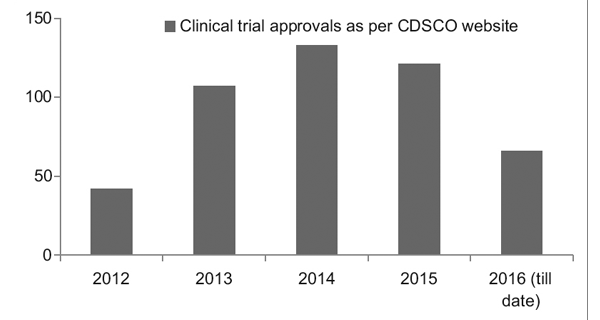

However, with a better regulatory framework in place, the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI) has recorded a steady rise in the number of trials being conducted, as seen in Figure 1. It was also observed that most of the trials were phase III trials.7

Figure 1: Clinical trial trends over the years

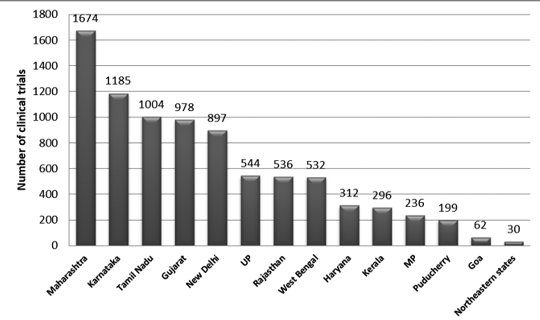

Figure 2 presents the state-wise distribution of trials in India between 2007 and 2015. Approximately 3330 trails were registered during this period.

It was observed that the maximum number of trials was conducted in Maharashtra, and the least number of trials was conducted in the Northeastern state. Among the Northeastern states, no trials were conducted in Nagaland.7

Figure 2: State-wise distribution of clinical trials in India (2007-2015 data)7

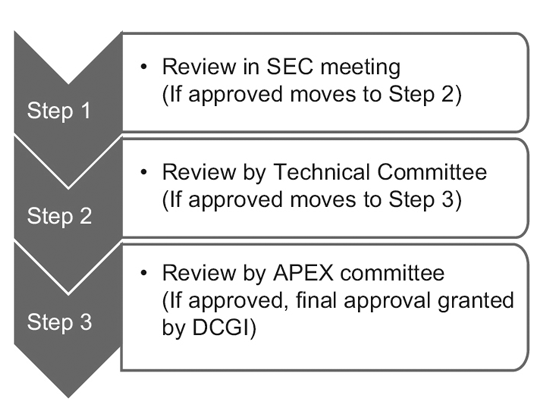

In 2014, the CDSCO constituted 12 new drug advisory committees (NDAC) and 25 subject expert committees (SECs). These committees have a number of experts from eminent government colleges and institutions to expedite the approval timelines of a clinical trial to 6-7 months.

The three-tier process consists of:9

However, only the SEC reviews global clinical trial applications, and no further approval is required from the Technical committee or the Apex committee. Investigational new drug (IND) applications are also reviewed independently by the IND committee and do not require the approval of the Apex committee.

A Technical committee comes into the picture only if the SEC has rejected a sponsor’s application and the sponsor feels aggrieved by the decision. In such an event, if the Technical committee disagrees with the decision of the SEC, it has the power to overrule the decision of the SEC.10

In March 2019, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India, released the New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules 2019 with the intention to fast-track the approval for clinical trials, new drugs, bio-equivalence (BE), or bio-availability (BA) studies.

These rules have also addressed any ambiguity that existed with respect to the regulation of the Ethics committee (EC).11

Highlights of the New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules, 201911 | Updated rules and regulations11 |

Approval timeline for clinical trials | 90 working days from receipt of an application for drugs discovered outside India and 30 working days for new drugs or IND in India |

Manufacturing of new drugs or IND, BE & BA studies or test analysis or examination | Permission is required from the Central Licensing Authority (CLA) |

Waiver of local clinical trials | · If CLA has approved the marketing of the new drug in other countries or has granted permission to conduct global clinical trials for the new drug in India · No evidence of a difference in metabolism, safety, or efficacy owing to the difference in the genetic profile of the Indian population |

Period of validity of a clinical trial | 2 years from the date of issue by CLA |

Post-trial access to IND or new drug | In unique circumstances, the drug is to be distributed free of cost to trial subjects per the direction of CLA, but no liability lies with the sponsor for the use of the drug after trial. |

Pre-submission and post-submission meetings | To seek guidance with respect to law and procedures that governs the process of manufacturing and licensing or granting permission. |

Approval for trials conducted by EC and registration of EC | · Approval to be obtained from the EC of another trial site if a trial site does not have an EC, and the EC should be within 50 km of the trial site.· CLA-approved registration of EC remains valid for five years from the date of issue. |

Conditions to be fulfilled for the conduct of a clinical trial | · Submission of status report on a quarterly basis or depending on the duration of the trial to track subject enrolment· Online reporting of the status of the clinical trial every six months via the SUGHAM portal to know if the trial is ongoing or completed or has been terminated. |

Fee for procuring a license, certificate of registration, and permission for trial | Different fee structures depending upon the purpose of the trial. Fee ranging from INR 50,000 to 5,00,000. |

The challenges of dealing with clinical trials are multi-faceted and involve abiding by the regulatory framework in a responsible and ethical way by stakeholders, government, and judicial system alike.

Patient safety and protection should be of utmost importance laying strict rules for:12

New ground rules that can open up the possibility of expanding medical research in India are:13

Proficient workforce and state-of-art infrastructure also play an important role in attracting sponsor companies. Research has demonstrated that though Phase III trials are being conducted in a big way in India, Phase I trials seem to be limited to the sponsor country.

This could be attributed to the Sponsor’s apprehension in procuring a qualified workforce and technology. To enable indigenous research to happen in India, it is pivotal to provide appropriate exposure or continuing medical education to personnel and access to up-to-date technology to be recognized as a country competent enough to conduct any phase trials.9

Equally important is the need for skilled healthcare workers to be available throughout the country to account for the uneven distribution of clinical trials across states.

Concentrating a trial on a particular state could lead to biased conclusions and oversimplify or exaggerate a disease burden or condition. By providing access to people in all states to join a clinical trial, we not only minimize bias but also include diverse ethnic populations.9

With positive, patient-friendly, fast-track, and transparent regulatory laws, India will continue to grow as an international hub for testing and developing innovative medicines and medical devices.

1. Evangeline L, Mounica NVN, Reddy VS et al. Regulatory process and ethics for clinical trials in India (CDSCO). The Pharma Innovation Journal. 2017;6(4):165-9. http://www.thepharmajournal.com/archives/2017/vol6issue4/PartC/6-4-4-176.pdf

2. Lahiry S, Sinha R, Choudhary S et al. Paradigm Shift in Clinical Trial Regulations in India. Indian Journal of Rheumatology. 2018;13:51-5.

3. Gogtay NJ, Ravi R, and Thatte UM. Regulatory requirements for clinical trials in India: What academicians need to know. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017 Mar;61(3):192-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5372399/

4. Ramu B, Kumar M S, and Ramakrishna N. Current Regulatory Scenario for Conducting Clinical Trials in India. Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs. Open Access. 2015;4:2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281765214_Current_Regulatory_Scenario_for_Conducting_Clinical_Trials_in_India

5. Burt T, Sharma P, Dhillon S et al. Clinical Research Environment in India: Challenges and Proposed Solutions. Journal of Clinical Research Bioethics. 2014;5:6. DOI: 10.4172/2155-9627.1000201

6. Chaturvedi M, Gogtay NJ, Thatte UM. Do clinical trials conducted in India match its healthcare needs? An audit of the Clinical Trials Registry of India. Perspectives in Clinical Research. 2017;8(4):172-5.

7. http://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/news/CTRI_Newsbulletin_July-Dec_2017.pdf Accessed on April 23, 2019.

8. Bhave A and Menon S. Regulatory environment for clinical research: Recent past and expected future. Perspectives in Clinical Research. 2017;8:11.6.

9. Key Highlights of New Drugs & Clinical Trial Rules, 2019. Accessed on April 23, 2019

10. Dan S, Karmakar S, Ghosh B et al. Digitization of Clinical Trials in India: A New Step by CDSCO towards Ensuring the Data Credibility and Patient Safety. Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs: Open Access. 2015;4(3): DOI: 10.4172/2167-7689.1000149.

11. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/new-rules-sweeten-the-deal-for-clinical-trials-by-indian-pharma-cos/article26283499.ece Accessed on April 23, 2019.

The information contained in this article is intended solely to provide general guidance on matters of interest for the personal use of the reader, who accepts full responsibility for its use. Accordingly, the information in this article is provided with the understanding that the author(s) and publisher(s) are not herein engaged in rendering professional advice or services.

As such, it should not be used as a substitute for consultation with a competent adviser. Before making any decision or taking any action, the reader should always consult a professional adviser relating to the relevant article posting.

While every attempt has been made to ensure that the information contained in this article has been obtained from reliable sources, Veeda Clinical Research is not responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of this information.

All information in this article is provided “as is,” with no guarantee of completeness, accuracy, timeliness, or of the results obtained from the use of this information, and without warranty of any kind, express or implied, including, but not limited to warranties of performance, merchantability, and fitness for a particular purpose.

Nothing herein shall, to any extent, substitute for the independent investigations and the sound technical and business judgment of the reader. In no event will Veeda Clinical Research, or its partners, employees, or agents, be liable to the reader or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information in this article or for any consequential, special, or similar damages, even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

For information, contact us at:

Veeda Clinical Research Private Limited

Vedant Complex, Beside YMCA Club, S. G. Highway,

Vejalpur, Ahmedabad – 380 051,

Gujarat India.

Phone: +91-79-3001-3000

Fax: +91-79-3001-3010

Email: info@veedacr.com